If I could make days last forever,

if words could make wishes come true,

I’d save every day like a treasure and then,

again, I would spend them with you…

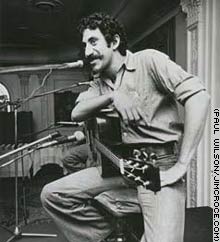

Jim Croce died in a plane crash more than 30 years ago just as his long-delayed career started to finally flower. Croce was one of the last folk-music singer/songwriters to become popular in 1972, as pop tastes were already changing to more synthesis and production. He barely had time to score two hit singles, “You Don’t Mess Around With Jim” and “Bad Bad Leroy Brown” before being killed, along with his musical partner Maury Muehlheisen.

By any logic, Croce should have been a footnote in musical history, but a strange thing happened: people suddenly couldn’t get enough of him. A string of hits followed, most poignantly “Time in a Bottle”, which talked about the precious moments in life and how soon and suddenly they pass. The hits ran out three years after his death, when the small catalogue of his recordings was finally exhausted.

Now Ingrid and A.J. Croce, his wife and son and a fine musician on his own, have regained the rights to the Croce catalog and have produced a DVD of what film can be found of Jim Croce, along with a re-release of his first album, recorded under fairly primitive conditions but which will be a treasure to fans of his music:

During a three-hour session at a Delaware studio, Croce and his friends laid down 11 tracks, almost all on the first take. The sound is raw: There’s an echo to Croce’s voice, breathing from the ensemble — even street sounds because the studio windows were left open because of the heat, Ingrid Croce says.

“There were no overdubs,” she says. “What you hear in ‘Facets’ is exactly what you get.” …

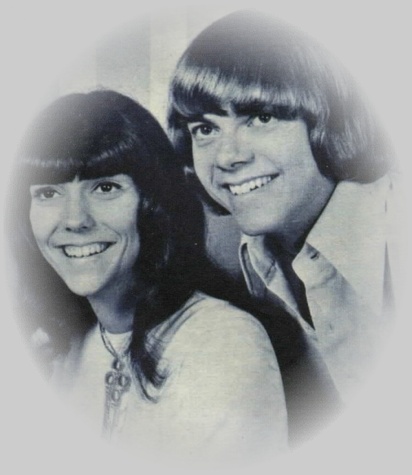

A bonus disc titled “Jim & Ingrid Too” features a smoother Croce voice partnered with his wife. (The couple met when Ingrid auditioned with her band at the radio station where he worked.) The seven tracks also have little production effects, but show off the couple’s natural knack as a duo.

I bought a copy of “Jim & Ingrid Too” twenty years ago when I found it at a garage sale, and I still have it today. It’s very much a product of its time, with sweet vocals and a bit too much earnestness about society — and undeniable talent. That album is one of the main reasons I still own a functioning turntable.

My first experience with Jim Croce came more than twenty-five years ago when my cousin Cris (who reads this blog) bought me the definitive Croce album at the time, “Photographs and Memories,” which showcased Croce’s skills as storyteller, musician, songwriter, and singer. With one exception — “I Got a Name” — he wrote every song on the album, and in fact most of his recordings were of his own compositions. He could play honky-tonk rock and switch immediately to heartwrenching ballads. Like the Carpenters, the easy accessibility of his music has led people to underestimate his contribution, especially when all that people recall of him is “Leroy Brown”.

For me, Croce’s songs, wise-cracking yet identifiable characters, and gentle wisdom became emotional guideposts. I played his music so often I could recite all of his lyrics by heart. When I moved to Phoenix at 29 knowing no one, the song “New York’s Not My Home” never went far out of mind. I have other favorite artists, such as Eric Clapton and the Cowboy Junkies, but none with the emotional tie I have to Jim Croce and his music.

I have done my best to find out as much as possible about him, especially earlier on. Every time I went to a record store, especially the rare-record boutiques, I’d browse through to see if there were any Croce albums that I hadn’t yet bought. In college, when I discovered the microfilm vault at the library, I spent hours searching for news articles on Croce, and found only a scant few. Despite all the talk about one, it still hasn’t been published. I even went to Croce’s in San Diego to see the memorabilia and to have an excellent meal. (If you ever get to San Diego, it’s definitely worth your while to try it.)

Since a biography has never been written, the DVD and the materials described in the article will be the best that fans can get. Hopefully, the new releases will give more people an opportunity to hear the fullness of Jim Croce’s work and to re-evaluate his contribution to music, which held so much promise — and was cut short all too soon.

But there never seems to be enough time

to do the things that you want to do

once you find them …